“You mean I get to take an extra two weeks off from school?”

That was my reaction to my mother’s directive that I and my sister volunteer with Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charities organization in Kolkata, India, for four weeks in 1994: the last two weeks of December and the first two weeks of January.

I was too young at 14 years of age to really grasp the reality of what she was telling me. All I focused on was, wow, two weeks off from school! My mother actually wanted this to happen!

Let me go ahead and explain one thing: In the Indian culture, parents will even sometimes make you go to school while you’re sick.

So getting sanctioned time off for school? Yeah, that was a new event for me.

Little did I know that those two extra weeks off, coupled with the preceding two weeks, would be the some of the most formative four weeks of my young life to that point.

Several inquisitive minds might inquire as to how a devout Hindu family like mine came about to experience such a decidedly Christian Catholic event.

To fully understand, one must understand the relationship between other religions and Hinduism. Within that context, one must then understand my family and its relationship to religion.

But, let us start with the overarching principle first.

Hinduism is such an ancient religion — estimated to have originated in 1500 BCE — that other religions are merely deemed “cute” and some are even considered to be a little part of this religion.

Christianity is one of these “gray area” religions to some Hindus.

In the Hindu religion, Lord Narayana — one of our main three gods — tended to reincarnate as demigods on Earth. The legends are this happened ten times, what Hindus call “Dasha Avatar.”

“Dasha” means “ten,” and “Avatar” means “Jim Cameron movie that is an unfunny parody of ‘Dances With Wolves’.”

Just kidding! “Avatar” means “divine reincarnation.”

One of the ten avatars of Narayana is considered to be Krishna, who I’m sure is most familiar to most of this audience.

There is an avatar slot out of the ten that most consider to be Buddha, but there is a decently-sized minority that believes that none other than Jesus Christ of Nazareth himself was that avatar instead. A construct did not exist within the Hindu dogma that excluded someone like Jesus from being holy.

That should provide enough context for people to see that there really is a thin, if any, dogmatic barrier between acceptance of the Christian faith by the Hindu faith.

The other bit of personal context that’s lacking for this story is my own family’s relationship with other religions.

I remember going to my parent’s study when I was a child and seeing, placed right next to each other, the Baghavad Gita, the Q’uran, and the Holy Bible.

In fact, I had a child’s record player when I was a kid, and the only record I even had for the thing at first was a recording of the Holy Bible that was accompanied by a comic book of the recording.

(Those who truly know me should not be surprised that the comic book was the big draw.)

It is a household tradition of ours — and many other Bengali Hindus — to offer a prayer to the Gods when you leave the house to ensure a safe journey. To this end, many Bengali Hindu households place statues of Gods and Goddesses near the main entry.

In our house, a crucifix has almost always accompanied the rest of our statues in the entryway.

When I first the discrepancy among in our religions, I brought it up to my mother, and this was her her response:

“Jesus was a man who did great things for people, and he may have even been holy.”

That was a good enough answer for me.

Traveling to India is an ordeal, but one that I have undertaken ever since..well, ever since I can remember! I always did joke that I felt like I was born on a plane.

You can usually go two ways to India from the US, and it is about the same amount of flight time: via a western route or via an eastern route.

Simple enough, right? Technically, any global location is accessible by traveling either west or east. But, I don’t remember which way we went on this particular trip.

Our first order of business once we got situated: meet Mother Teresa at her Missionaries of Charity and offer to volunteer.

My mother did not make an appointment, did not call ahead, and did not feel such preparations were necessary. This was merely a walk-in appointment to ask for permission to volunteer for a month.

The Missionaries of Charity building itself isn’t impressive. It’s not some big homage to gothic architecture, but rather a non-descript building with countless rooms. It, however, was not exactly a stale office building either as it contained courtyards and Sisters bustling from corner to corner.

We sat quietly waiting for Mother Teresa to come out. I actually did not really expect her to even greet us — people that busy usually send out delegates to handle this sort of thing — but lo and behold, she emerged from the crowd of nuns to talk to us once she was alerted of our presence.

Mother Teresa was extremely diminutive physically. I couldn’t imagine she was an inch above five feet tall. More than likely, she was several inches below that mark.

But, that did not stop her from approaching us.

Once we shook her hands, my mother explained to her that I was 14 years old, not quite yet the requisite level of 16 years old for her organization. The latter fact was pointed out to to Mother Teresa by a nun that had overheard our conversation.

“If he wants to work, let him work,” Mother Teresa told both the nun and my family, all while still holding my hands.

So, work we did.

My mother initially intended for all three us for to volunteer at an orphanage called Shishu Bhavan — which translates to “House of Children” — but they had a strict policy against allowing males to work in the orphanage. Volunteering was limited to only females as there had been security issues with males in the past.

I was not offended by any means. Rather, I felt sad that some men acted in such a way that this rule had to be enacted in the first place.

Instead, we set off to volunteer at Prem Dan, a homeless shelter whose name translates to “Gift of Love.”

Prem Dan was located in the Park Circus/Ballygunge section of Kolkata, a morning train ride for us every day. We would get up at 5 AM, get ready, walk to the nearest train station, navigate the burgeoning crowds to safely secure a spot on a quickly moving train, put up with a few minutes of practically no personal space, and then disembark at Park Circus/Ballygunge.

The shelter itself was situated very very close to the station. In fact, once the trains cleared from view, you could see the slums that surrounded the shelter in plain sight.

I have always felt that you notice different things at stages in your life, mainly due to personal context.

What I always noticed about these slums each morning was that, though the children always playing outside were dirty and tattered in rags, they were always laughing loudly.

That is something that I kept with me as I volunteered each and every morning for a month at Prem Dan.

Life is often what you make it, and it feels good to laugh even when others think you have no reason to be happy.

As was the case in almost any center run by the Missionaries of Charity, the men and women were located in separate sides of the complex. You had to work with your own gender — in the binary sense — for security purposes, much like the aforementioned Shishu Bhawan.

My days were spent doing a daily combination of laundry, mopping, patient baths, and patient feeding.

Laundry was by far the most grueling of the tasks. There were no washing machines at all. Instead, clothes were boiled in hot water, and then the dirt was beaten out of each and every garment before we hung them out to dry.

For someone who, quite honestly, at this point in life still had his mother taking care of his laundry, this was a jarring to contrast to my usual chores.

This was also the first time I had ever mopped a floor in my life. There really is not too much to say about that particular task. If you’ve mopped one dirty floor, you’ve mopped them all. I suppose there are degrees to consider within that statement, but let’s just say these floors were quite dirty.

I did have to bathe the patients. Although nowhere near a physically taxing as laundry, this was my least favorite task of them all. It was too intimate for my tastes. I did not know these people — many of whom had soiled themselves — and here I was scrubbing very close to their private areas.

Feeding everyone, on the other hand, that was what I looked forward to each and every day.

The food always smelled pretty good! For some reason, that was a surprise to me, though reflecting on it now, I really should not have been as shocked as I was.

The menu was always typical Bengali fare: lentils, rice, potato curry, and sometimes some chicken curry.

This was not exactly the reason why this part of the day was my favorite.

The reason why this was my most favorite part of the day?

This was the time I had to sit and talk to all the patients in a more relaxed setting without the bustle of cleaning them.

I really got the sense there that they were content there, that life in the shelter was far better than anything the situation that landed them there. This, of course, excluded the mentally ill patients, of which there were more than a few.

I heard stories from the patients and the other volunteers of how so many of the people there were put out on the street by their own families when it grew too tiresome — mentally and financially — to take care of them.

Many of the patients there were mentally ill. I remember there was this man — he may have been in his 60s when I was tending to him — who looked like he may have originated from the more Asiatic side of India as he had East Asian facial characteristics. He would not speak much, but that never stopped from him constantly smiling. He had a habit of saluting me every time he saw me, the British method with the palm facing outward. I would call him “The General” as a result. As a teenager, it was very amusing to be saluted every day while I bathed a man who couldn’t take care of himself. Those were our only interactions, but I remembered thinking that I was glad someone of his condition and age was being taken care of by the nuns.

That is not to say all the patients were of senior age. Though that might have the been the majority demographic, there definitely were a few younger patients.

One such younger patient — he might have actually been about five years older than me — always liked joking with me as I was the only one there who was even close to his age. He even taught me a “little” Hindi in my time there. I put “little” in quotation marks for a simple reason: the word he taught me was “thorah,” which means “little” in Hindi.

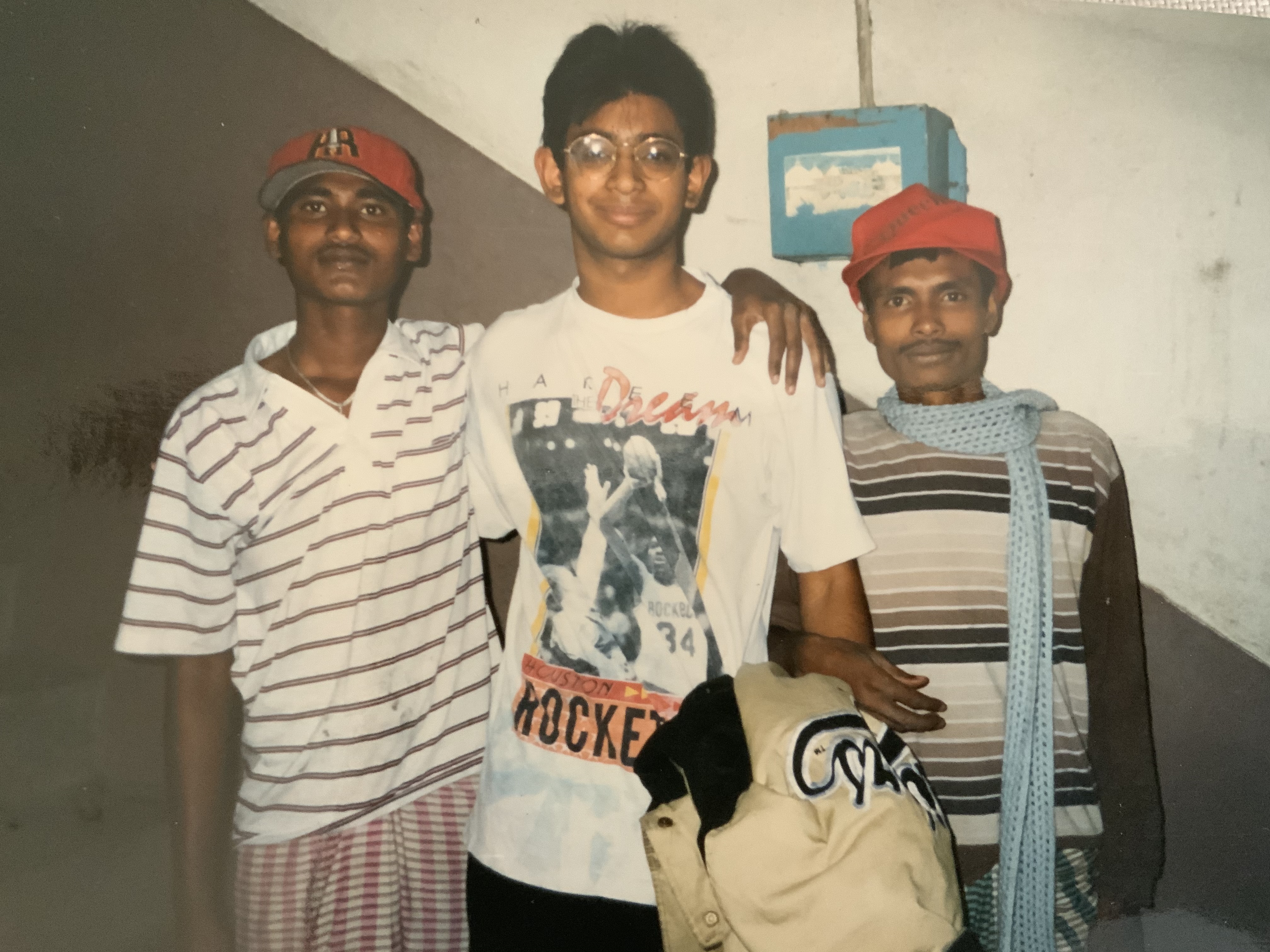

When my time there came to an end, I gifted him my Houston Rockets cap that I had worn all through my time there. He was just ecstatic to receive it, as he had always told me how much he liked how it looked.

It was the least I could do. My time spent there observing and talking to everyone imparted me with considerable lessons in such a relatively short amount of time.

It was nothing you could really learn in school.

My mother’s and sister’s duties at Prem Dan practically mirrored mine. They too were bathing, feeding, administering medicine, and conversing with all the people taking refuge there.

Of course, the women — mostly Bengali — had their own cast of characters on their side.

(Though my mother may be getting up in age, she has the same knack I do for remembering small details that ultimately end up mattering. Most of this commentary is transcribed from her talks with me, and my sister also did a fantastic job of confirming events and fixing whatever gaps we had in our memories.)

One of these characters was nicknamed “Balugh,” which means “bear” in Bengali. She was the quintessential “wild child” story, as in, she was rumored to have been raised by animals in the forest.

Saint Teresa apparently went to Madhya Pradesh — a state smack dab in the center of India — many years ago and found two girls in the forest, both aged around five or six years old, that were harvesting whatever food they could from the forest floor. The nuns saw bears in the distance when the girls were spotted, but, even with the constant rumors from the nearby villagers, there was no actual confirmation that the children were raised by any animals.

Sadly, one of the little girls perished soon after the nuns admitted them into a hospital to recover from malnourishment and dehydration, but Balugh survived. Saint Teresa then brought the surviving child with her to Kolkata to stay at Prem Dan.

There was not much else to tell of Balugh’s story, save for one small quirk: she had an irrational fear of the color red.

(You may be tempted to compare this to the common sentiment regarding bulls, but keep in mind that this is an old wives tale of sorts as bulls are red-green color blind and cannot even distinguish the color red!)

Another lady who caught my attention there was nicknamed “Jol Khabo” — “I’ll Drink Water” — as that is the only phrase she would say, and she would repeat it incessantly. She did not even know her own name, or at least, she did not tell it to anyone. She frequently made erratic physical movements and clearly was suffering from a neurological disorder of some sort.

Combined with Balugh, Prem Dan definitely had its share of mentally ill patients on the women’s side, much like the men’s.

Of the more sane ladies, there was one who spoke with a British accent and claimed she had a British father, but her features seemed strictly Indian with no real outside influence.

Another woman there had been displaced due to The Partition of India, a violent period of Indian history — mostly in the border states Bengal and Punjab — that took place right after Independence and was rife with religious conflict. She was a Bengali Hindu whose house was burned down by Muslim rioters. And, here she was in Prem Dan with us all those years later, with nowhere else to go.

Between the two sides, men and women, there was no shortage of work for us to do. More importantly, there was no shortage of happiness from seeing others directly benefit from the hard work we did.

I’m still sure those four weeks in India were a better experience than anything I could’ve done in those two weeks of missed school.

Now that I’ve explained what our experiences were like volunteering with Saint Teresa and her Missionaries of Charities, I’d like to address a few controversial topics.

When I first was offered the option of volunteering with Saint Teresa, my initial and primary concern was religion. I was still finding my own spiritual way at that time — really, though, we are all still finding our spiritual way through each step in life — I knew that I did not want to witness any sort of forced conversion.

I really was hoping that we were not volunteering at a “SOUL-FOR-SHELTER” type of facility.

To that end, I personally only heard one small mention of religion on the men’s side. One man in his 20s said that he converted from Hinduism to Christianity at their suggestion, but he admitted to not being all that religious in the first place. That was really the only religious talk I heard.

That was reassuring, quite honestly. It was one less thing for me to worry about.

On the women’s side, however, my mother met an elder Hindu widow from Bangladesh at Prem Dan whose food was served to her separately.

When my mother asked the presiding nun why the widow was being served separately, the Sister replied that they were accommodating her religious diet with a separate meal. Which, honestly, is considerate.

That being said, my mother and sister did relate one story to me that made me pause and consider the religious side of Prem Dan.

Apparently, once a week, the Sisters would ask the non-Christians if they want to convert. It seems that different patients there had different experiences with this. One woman said a nun was telling her that she HAD to convert, while another woman had a softer story: the Sisters would ask you to convert, and if you refused, they would remind you that Christians took you in while Hindus/Muslims/Buddhists did not.

It was a proselytizing guilt trip.

But, something that I think is important to mention: no one’s life was made worse if they said ”no.” I mean, sure, they did ask for conversions frequently apparently, but there was no retaliation of any sort for refusal.

Look: they are missionaries. Their title is even The Missionaries of Charity. A missionary’s job is to proselytize. I get that.

I am just glad that it wasn’t the basis of receiving care.

I understand that there seems to be a subtext of global controversy attached to Saint Teresa, especially in regards to her practices with hospice care and not allowing dying patients to take painkillers.

This controversy has gotten so out of hand that one person made an offhand comment to me on how Saint Teresa was a “trash person.” Another respected friend of mine unfortunately was holding on to the view that Saint Teresa was a “monster” due to this controversy.

I personally do not know this controversy as I did not work in a hospice during my time with the Sisters.

What I do know — and have personally witnessed — is that Saint Teresa and her Missionaries of Charity helped out literally hundreds, it not thousands, of destitutes and refugees at Prem Dan when the poor souls had nowhere else to turn to for the basic necessities of life, like comfort and food.

Their souls were not being held ransom for care. I also never heard word of anyone mentioning any type of abuse at any of her charity centers.

My mother had a more personal exchange with Saint Teresa than I did, and she let me know that all Saint Teresa really was interested was getting medical supplies for her people in need.

“You can only help me with medicine,” the diminutive nun told my mother.

“We need lots of medicine.”

I am not saying that Saint Teresa is above reproach.

Frankly, no one is.

I only ask that people weigh her apparent misgivings against all the good she did for people who had nowhere else to turn.

I only ask that, before you resort to calling her a “monster” or anything similar, you consider whether a “trash person” could really have taken the literally thousands of homeless people in Kolkata, India, and given them shelter and food.

Sure, you can beat the missionary drum and say that she was just interested in conversions, so that is why she created an organization to help the sick, the homeless, and the children.

As I mentioned earlier in my story, I even held this concern myself.

But, it was unfounded.

Saint Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity continue to do great work in and around Kolkata.

I know that I myself am very grateful for the work they do, and I’m sure the thousands of patients they take care of at Prem Dan are grateful as well.

I am also very grateful my mother let me miss those two weeks of school to experience a personal growth that would not otherwise have been afforded to me.

This is dedicated to my mother Minakshi Ghosh as none of this would have been possible without her efforts and foresight.

— Shameek Ghosh, May 8, 2021

The following pictures are others that were taken of Shameek Ghosh and the patients at Prem Dan